Hi, I’m David. I’m a trademark lawyer, avid kite-surfer and generally regarded as a great guy (Ed.: unverified opinion, but we’re letting it go). That’s my personal brand. My firm, Clark Wilson LLP, a for-profit enterprise, has a brand and a logo that you’ve already seen and can find on this very page.

Educational institutions also have brands and logos, which can be as simple as the institution’s name in a unique script, or more complex, like flashy designs and a fuzzy or feathered mascot. When it comes down to protection of this type of intellectual property, we’re talking “marks”—but there are lots of words used to describe these marks (here’s a list of 20 different categories of marks). In the context of the post-secondary sector, there are, thankfully, three that are of primary interest: trademarks, official marks, and prohibited marks.

What do these terms mean? What’s the difference? Read on.

Trademarks

Many businesses use trademarks to distinguish their goods and services from the competition. Consumers then associate positive experiences with some brands and negative experiences with others.

This provides some practical benefits: if you’re hungry while on the road, you can decide between the major name-brand restaurants, or you can decide to grab something familiar like a Big Mac® at McDonalds®, or try your luck at some strange new place called “Houston Pete’s Family Feedbucket and Armory”.

A mark that is actually used in association with goods or services may automatically be protected (we say that “rights arise through use”), but you can also apply to register your trademark. If granted, a registration affords a special kind of right to the owner: protection across Canada (without having to prove a nation-wide market presence). Once registered, however, trademark registrations must be maintained through periodic renewal fees. Registrations can also be challenged for non-use, and if challenged, will be cancelled if an owner fails to file evidence showing use.

In the commercial, for-profit business world, the vast majority of marks you see are trademarks (most are registered and show the ® or ™ sign, though the Trade-marks Act does not require that trademarks be marked in one or the other way, or at all).

Prohibited Marks

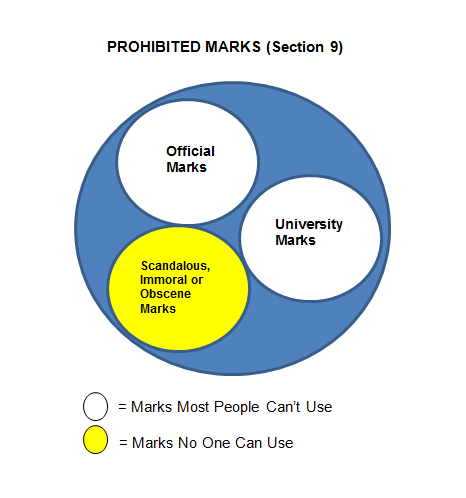

In addition to trademarks, Canadian law also recognizes a broad category of “prohibited marks.” Prohibited marks are exactly what they sound like: marks that people are prohibited from adopting as trademarks or using in connection with their businesses.

There are different types of prohibited marks, and many are not prohibited for everyone. For instance, some marks are generally prohibited, meaning that no one can use them. The Canadian Trade-marks Act, for instance, prohibits everyone from adopting or using “any scandalous, obscene or immoral word or device”. This category is, of course, incredibly subjective. I will stop short of providing examples of such marks in this article, but I’m sure you can imagine several examples yourself.

Other marks are prohibited for almost everyone, except for certain special people. Canada is, of course, a constitutional monarchy – as our printed money insists on reminding us. It will come as no surprise, then, that the Trade-marks Act prohibits businesses from adopting or using the Royal Arms, Crest or Standard, as well as the arms or crest of any member of the royal family.

More likely than not, you are not a member of the Royal Family. However, if you work for a university, you should know that the Trade-marks Act also prohibits businesses from adopting or using any badge, crest, emblem or mark of any “university”. A University in Canada can give public notice of its mark, and use this public notice to prevent other businesses from adopting confusingly similar marks. See here for our earlier article, discussing the advantages of Prohibited Marks for Universities.

Official Marks

If you are an educational institution other than a university, such as a college or institute, then under the Trade-marks Act, you may be entitled to protection in the form of an official mark. Official marks are also prohibited marks, but they can be adopted by a “public authority”, rather than a university. While both university marks and official marks are prohibited marks and afford equivalent protections, they technically differ. A good way to illustrate this is through the following picture:

Not every educational institution that is not a university is entitled to an official mark. First, the institution must operate for the benefit of the public. Second, the institution must be under a significant degree of control by a government in Canada. Most public educational institutions that are not universities easily satisfy the first element. The second element can be more tricky. Usually sufficient government control is shown through evidence of a variety of factors. A good sign that your non-university educational institution is a public authority is that a federal or provincial Minister has the ability to:

- review your institution’s activities;

- recommend that your institution undertake necessary additional activities;

- advise a board or council on the implementation of a statutory scheme;

- approve the exercise of your institution’s regulation-making; and

- appoint members to the institution’s board or council (it does not need to be a majority).

Your institution does not need to satisfy all of the factors above, however, the more this list describes your institution, the more likely the institution is to be considered a “public authority”.

Official marks can be more convenient than regular trademarks. For instance, official marks are “advertised” in the Trade-marks Journal rather than registered, so the mark will remain on the Register indefinitely, without need to renew it. Further, official marks typically cover all goods and services, so any person applying for a confusingly similar trademark in the future may need to seek your permission for registration, regardless of the goods or services which they seek to provide in association with the new trademark. See here for our earlier article, which gets into more detail about the advantages of Prohibited Marks for Universities – that article would read exactly the same if we put it in the context of Official Marks and public authorities.

Which are right for my institution?

Trademarks can offer certain advantages that prohibited marks cannot, including specific causes of action (e.g. owners of registered trademarks can sue for “depreciation of goodwill”) and border enforcement mechanisms.

Therefore, an effective trademark strategy will make use of both types of marks, which will help keep those fuzzy mascots safe and sound (and meeting your objectives, not someone else’s).

This article is the second in a series about trademarks focused on the Canadian post-secondary sector. If you have any questions or ideas for where to take this series, please contact the writers.

Next time: Cease and Desist Letters in the Age of Social Media, which will include tips and tricks for enforcing your rights without creating a public relations fiasco.