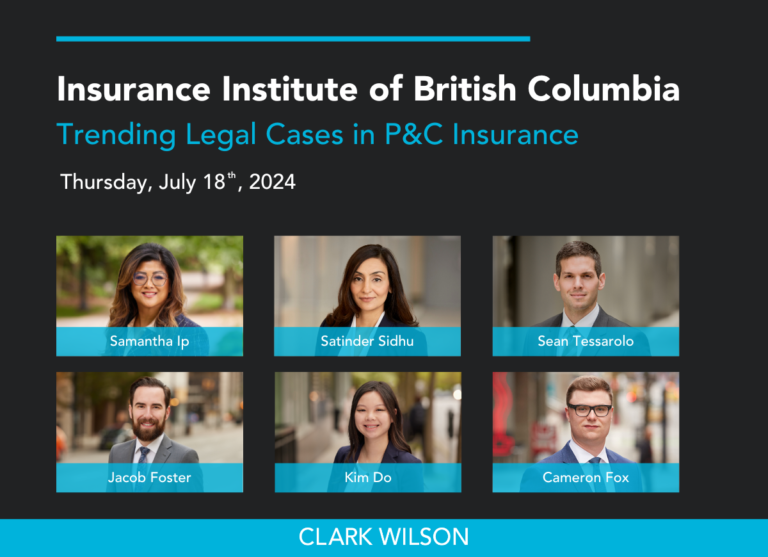

By Kim Do

The BC Court of Appeal delivered yet another reminder to insurers that, when interpreting policy wording, the policy must be read as a whole and the analysis must not be reduced to specific words viewed in isolation. Failing to do so may result in arriving at an incorrect coverage determination, as was recently seen in Gill v The Wawanesa Mutual Insurance Company, 2023 BCCA 97 [Gill], where the Court of Appeal found a water back-up on a partially enclosed sun deck was “within [the] dwelling” and found coverage for the insured.

Background

In Gill, the homeowners claimed coverage under their all-risks policy (the “Policy”) after water backed up and escaped from a drain located on the sun deck of their property, causing damage. The Policy excluded coverage for loss or damage caused by water or sewage backup, but contained a Sewer Backup Endorsement (the “Endorsement”) for damage caused by a sewer backup “within [the] dwelling”, as follows:

… “you” are insured against direct physical loss or damage to property … caused by “sewer backup”.

…

“Sewer Backup” means the sudden and accidental backing up or escape of water or sewage within your dwelling or detached private structures through a:

> Sewer on your premises …

The Policy defined “dwelling” as “the building … wholly or partially occupied as a private residence”.

The sun deck where the back up occurred was partially open to the outdoors. The insurer admitted it was part of the dwelling, but denied coverage on the basis that it was not “within” the dwelling to trigger the Endorsement.

Summary Trial

The trial judge agreed with the insurer and dismissed the homeowners’ claims, finding that the average person applying for insurance would understand the phrase “within [the] dwelling” to mean inside the dwelling or the house, which did not include areas outside the exterior walls. An average person viewing the sun deck would immediately know and understand it to be outside the exterior walls, and therefore not “within [the] dwelling” to trigger the Endorsement. The homeowners appealed.

Appeal

The homeowners were successful on appeal. In overturning the trial judge’s ruling, the Court of Appeal restated the well-established principles that apply when interpreting insurance policies, including:

- The primary interpretive principle is that when the language of the policy is unambiguous, the court should give effect to clear language, reading the contract as a whole.

- Determining whether the language of a policy has a clear meaning should be from the perspective of how the words would be understood by the average person applying for insurance, as opposed to insurance law experts.

- Where the language of the insurance policy is ambiguous, the courts rely on general rules of contract construction. For example, courts should prefer interpretations consistent with the reasonable expectations of the parties, so long as such an interpretation can be supported by the text of the policy, and should avoid interpretations that would give rise to an unrealistic result or that would not have been in the contemplation of the parties at the time the policy was concluded. Courts should also strive to ensure that similar insurance policies are construed consistently.

- If these rules of construction fail to resolve the ambiguity, the courts will construe the policy contra proferentem against the insurer. Coverage provisions are interpreted broadly, and exclusion clauses narrowly.

In this case, the trial judge had erred by failing to interpret the Policy as a whole and misapplying the average person’s perspective. The trial judge had interpreted the words “within [the] dwelling” in the Policy from the perspective of an average person engaged in conversation about what was inside their house, and not the average person considering the coverage afforded by the Policy. That “average person” would have been erroneously disconnected from the language of the Policy.

The Court of Appeal found that, when read as a whole and from the perspective of the average person applying for insurance, the language of the Policy had a clear meaning. In particular, the Policy’s other wording shed light on the ordinary meaning of “within [the] dwelling” as it provided coverage for back up occurring “within [the] dwelling” and in “detached private structures”. “Detached private structures” was not defined by the Policy, but nothing implied it was only a structure entirely enclosed by four walls. Further, the word “dwelling” was defined in the Policy as the building, which included the sun deck. The insurer had already admitted the sun deck was part of the dwelling.

Instead of focusing on the plain language of the Endorsement, the trial judge incorrectly reduced the analysis to one that turned on the word “within”, taking it to mean “inside” or “indoors”. However, “within” did not necessarily mean “indoors”; it simply asked, within what (for example, being “within” Canada could mean being somewhere on the map, but not necessarily indoors.) “Within [the] dwelling” expressed a spatial relationship with the dwelling, and based on how “dwelling” was defined in the Policy, the sun deck was “within [the] dwelling”. To conclude the sun deck was part of the dwelling (as conceded by the insurer) yet also entirely outside of it (as argued by the insurer) would be “inconsistent and nonsensical”.

Turning to the average person purchasing insurance, if such person was told the Policy defined the dwelling as the building and the building included the sun deck, and the person was then asked whether the drain on the sun deck was “within [the] dwelling”, the answer would be “yes”.

Takeaway

Gill serves as yet another reminder to insurers that coverage analysis and interpreting provisions in standard form policies requires the policy be read as a whole. Endorsements to a policy are no exception. Failing to do so may result in reducing the analysis to the meaning of specific words, conflating words and their meanings, and arriving at incorrect coverage determinations, disconnected from the policy’s words.