A. INTRODUCTION

Once again in 2016 there has been no progress to bring into force the significant amendments passed in 2014 to the Trade-marks Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. T-13 (the “Act”) and corresponding amendments to the Trademarks Regulations (SOR/96–195) (the “Regulations”), on which we have previously reported.

However, there was one amendment of significance to the Act passed in 2015 that was brought into force in 2016 regarding the extension of privilege to trademark agents.

There have been some interesting decisions of the Federal Court and Federal Court of Appeal in 2016, including a decision regarding trademarks comprising a geographic name, which also precipitated a Practice Notice to be issued by the Canadian Intellectual Property Office (“CIPO”). Other decisions of note discussed in this chapter include a number of decisions involving the granting of joinder as a party or intervener status in proceedings under s. 45 of the Act, a decision reviewing personal liability in trademark counterfeiting actions, and decisions regarding false and misleading statements pursuant to s. 7(a) of the Act.

This article was originally published by The Continuing Legal Education Society of British Columbia in their “Annual Review of Law & Practice – 2017”.

B. LEGISLATION

1. Amendments to the Trade-marks Act

a. Bill C-31, Economic Action Plan 2014, No. 1

As reported in last year’s edition of the Annual Review, the significant reforms to the Act given Royal Assent in 2014 are not anticipated to be brought into force until late 2018.

b. Privileged Communications

On June 24, 2016, s. 51.13 of the Act came into force whereby the common law concept of privilege between lawyers and their clients was extended in an amendment to the Act to apply to trademark agents. This privilege protects confidential communication between trademark agents and their clients from disclosure and use in legal proceedings. The amendment arose from Bill C-59, which was given Royal Assent in 2015.

Pursuant to s. 51.13 of the Act, privilege may apply to a communication that is:

- between an individual whose name is included on the list of trademark agents and that individual’s client;

- intended to be confidential; and

- made for the purpose of seeking or giving advice with respect to any matter relating to the protection of a trademark or other marks under the Act;

Such privilege belongs to the client and can only be waived, impliedly or expressly, by the client.

Pursuant to the amendments, privilege under Canadian law extends to trademark agents in a foreign country and their clients if:

- the foreign country’s laws also recognize privilege in the communications; and

- the communications would meet the requirements for privilege in Canada had they been made between an individual whose name is entered on the Canadian Register of Trademark Agents and that individual’s client.

In terms of transition, if a communication was confidential prior to June 24, 2016, and remains so thereafter, it will be treated as privileged if it falls within the statutory requirements.

It will likely be left to the courts to determine the scope of this new statutory privilege as there is potentially some ambiguity in the scope of protection given to “any matter relating to the protection of a trademark” in s. 53.13 of the Act. However, it is clear that drafting of trademark applications and preparation of responses to office actions will be privileged.

In any event, trademark agents are strongly recommended to assert privilege by marking documents “privileged” or “trademark agent privilege”.

2. Amendments to the Quebec Charter of the French Language

On November 24, 2016, the Quebec government brought into force amendments to the Charter of the French Language in Quebec. These amendments are aimed at ensuring the presence of French where commercial signs and posters display trademarks exclusively in a language other than French.

The detailed amendments do not require that non-French trademarks be translated into French or modified to include a French-language generic modifier. What is required is a “sufficient presence of French” on the sign or nearby.

It appears that the presence requirements could be fulfilled by adding to a sign a French generic term or description of the product or services, a French slogan, or other information in French about the products or services offered (excluding hours or addresses of the business).

These new regulations apply immediately to any new business and existing businesses will have three years to comply.

3. International Treaties

a. Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement

In the previous two editions of the Annual Review, we reported on the details and progress of the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement between the European Union (“EU”) and Canada (“CETA”).

On October 30, 2016, Canada and representatives of the EU signed CETA but final ratification is still required by the European Parliament and the legislatures in each EU member legislature. This ratification by member countries of the EU may take years.

However, the EU Parliament is expected in February of 2017 to ratify CETA. If passed by the EU Parliament, approximately 90% of the provisions of CETA will come into force, including the geographic indicator provisions about which we have provided details in prior editions of the Annual Review.

b. Trans Pacific Partnership

Last year we reported on the signing of the Trans Pacific Partnership trade agreement (“TPP”) by the 12 parties, including Canada. The TPP has significant provisions dealing with intellectual property, including trademarks. However, with the election of Donald Trump as President of the United States, one of the key signatories, it remains to be seen if the TPP will ever be ratified and brought into force by the parties.

C. ADMINISTRATIVE PRACTICE

1. Place of Origin—Section 12(1)(b) of the Act

On November 9, 2016, CIPO published a Practice Notice to clarify the application of s. 12(1)(b) of the Act, which prohibits the registration of trademarks that are clearly descriptive or deceptively misdescriptive of the place of origin of the goods and services in association with which the marks are used. This Practice Notice follows the Federal Court of Appeal decision in MC Imports Inc. v. AFOD Ltd., 2016 FCA 60, which we have reviewed in detail below. The Practice Notice gives guidance as to how the Examiners in CIPO will treat trademark applications with respect to s. 12(1)(b) of the Act.

A trademark will be considered a geographic name if it either: (1) has no other meaning; or (2) has multiple meanings, but has a primary or predominant meaning as a geographic name from the perspective of the ordinary Canadian consumer.

A trademark is deemed to be clearly descriptive of the place of origin if the trademark, whether depicted, written, or sounded, is a geographic name and the goods or services associated with the mark originate from the location of the geographic name.

However, a trademark is misdescriptive if the trademark is a geographical name and the goods or services associated with the mark do not actually originate from the geographic location. When assessing whether the trademark is deceptively misdescriptive, the Examiner of the trademark application must determine whether the ordinary Canadian consumer would believe that the goods or services originated in the geographic name referenced in the mark.

If a trademark is determined to be a geographic name, the trademark applicant will be requested to provide confirmation of the actual place of origin of the goods or services associated with the trademark.

2. Correspondence Procedure

On May 25, 2016, CIPO issued a Practice Notice updating its correspondence procedures.

The CIPO address for the Office of the Registrar of Trademarks is:

Canadian Intellectual Property Office

Place du Portage 1

50 Victoria Street, Room C-114

Gatineau, QC K1A 0C9

Correspondence delivered to this address during ordinary business hours will be considered received on the date of delivery. It should be noted that once correspondence is received by CIPO it cannot be returned to the sender, even if the sender states it was sent by mistake.

The designated establishment in Vancouver where correspondence may be delivered is:

Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada

Library Square

300 West Georgia Street

Vancouver, BC V6B 6E1

Correspondence delivered to a designated establishment on a day on which CIPO is closed will be considered received on the next day on which CIPO is open for business.

Correspondence delivered through Canada Post’s Registered Mail or Xpresspost services is received by CIPO on the day indicated on the mailing receipt provided by Canada Post, or if CIPO is closed, on the day when CIPO is next open for business.

With respect to electronic correspondence, there are a number of points to note. Correspondence sent by facsimile or online via CIPO’s website constitute the original, and duplicate paper copies should not be sent. Correspondence sent by electronic means will be considered received on the day transmitted if delivered before midnight on a day CIPO is open for business. If CIPO is closed for business, such correspondence will be considered received on the next day CIPO is open for business.

The following correspondence addressed to the Registrar of Trademarks may be sent electronically via CIPO’s website by accessing the following webpages:

- filing a new or revised trademark application;

- renewal of a trademark registration;

- request to enter a name on a list of trademark agents;

- annual renewal of a trademark agent;

- requesting copies of trademark documents;

- filing of a declaration of use;

- registration of a trademark application;

- registration of a statement of opposition; and

- extensions of time in trademark oppositions.

3. Pilot Project—Email Communications for Hearings

On August 30, 2016, CIPO announced in a Practice Notice a pilot project for the period of September 1, 2016, to March 1, 2017, to try to expedite communications of correspondence with respect to hearings in s. 45 and opposition proceedings.

During this time period, the Trademarks Opposition Board will provide parties scheduled for an upcoming hearing an email address to use to ensure timely communication of incoming hearing correspondence. The parties are to copy the other party on subsequent email communication in this regard. This does not provide an additional method of correspondence with the Registrar and parties should still follow the published Practice Notice for correspondence set out above.

D. CASE LAW

In 2016, there were a number of interesting decisions in the Federal Court on a variety of issues, including the following cases.

1. Confusion

Over the past two years we have reported on the ongoing battle between Cathay Pacific Airways Limited (“Cathay Pacific”) and Air Miles International Trading B.V. (“Air Miles”) with respect to opposition by Air Miles to registration by Cathay Pacific of the mark ASIA MILES as a word mark and four other design marks incorporating this word mark (the “Cathay Pacific Marks”). Air Miles opposed the application for registration of the Cathay Pacific Marks before the Trademarks Opposition Board on the basis that there was a likelihood of confusion between the Cathay Pacific Marks and Air Miles’ registered trademark AIR MILES.

In Cathay Pacific Airways Ltd. v. Air Miles International Trading B.V., 2016 FC 1125, the Federal Court re-heard de novo an appeal from the Registrar. This came about after the Federal Court initially allowed Cathay Pacific’s appeal from the Registrar’s decision to refuse registration of the Cathay Pacific Marks on the basis that the Registrar had come to an unreasonable decision based on the record before it.

This decision was appealed to the Federal Court of Appeal, which ordered that the matter be returned to the lower court to be determined on all issues based on a review of the new evidence submitted by Cathay Pacific to the lower court, which the lower court did not consider in making its initial decision.

On the second review of the Registrar’s decision, the Federal Court reversed its initial decision and dismissed Cathay Pacific’s appeal of the Registrar’s decision to refuse registration of the Cathay Pacific Marks. The Federal Court found that the new evidence submitted by Cathay Pacific would have potentially altered its view, but concluded that it did not change its overall conclusion to refuse to register the Cathay Pacific Marks.

While the Federal Court was critical of various aspects of the Registrar’s decision, the Federal Court came to the same conclusion as the Registrar on the key issue of whether there was a likelihood of confusion between the Cathay Pacific Marks comprising the word mark ASIA MILES and Air Miles’ registered trademark AIR MILES.

Specifically, the Registrar failed to address Cathay Pacific’s argument that Air Miles opposition based on s. 30(a) of the Act was insufficiently pleaded. In this regard, the Registrar should not have accepted Air Miles’ argument that the Cathay Pacific Marks were not used in a trademark sense for the goods as this was not pleaded in the statement of opposition.

As well, the Registrar erred in refusing the applications in respect of certain goods and services under s. 30(b) of the Act as it erroneously found that the Cathay Pacific Marks used by a subsidiary of Cathay Pacific did not accrue to Cathay Pacific.

With respect to the confusion analysis under s. 6(5) of the Act, the Federal Court agreed with the Registrar’s ultimate finding of likelihood of confusion.

The Federal Court agreed that the AIR MILES trademark possessed a fairly low degree of inherent distinctiveness as it comprised two common words. However, the Federal Court also agreed that the AIR MILES trademark was very well known, if not famous, in Canada.

While the Federal Court stated that the new evidence supported a finding that Cathay Pacific did acquire at least some distinctiveness in the Cathay Pacific Marks, this was not sufficient to overturn the finding on this factor in favour of Air Miles. The prior use of the AIR MILES trademark by Air Miles of about 13 years over the Cathay Pacific Marks was another factor favouring Air Miles in the analysis.

Further, the parties essentially operate the same sort of customer rewards program, which again was a factor in favour of Air Miles.

However, with respect to the key element of the degree of resemblance between the marks in issue, ASIA MILES and AIR MILES, the Federal Court found that they are “more different than alike visually and in sounding due to the different first words of the marks, although less so in ideas suggested”.

Despite the finding on this factor, the Federal Court agreed with the Registrar that Cathay Pacific Marks were “not sufficiently different from Air Miles’ well-known mark, nor acquired a sufficient reputation in its inherently weak mark, to make confusion unlikely”.

This finding is significant given that there was no evidence of actual confusion between the marks despite co-existence in the marketplace since 1999. Further, the marks in issue contained a common element that is also contained in a number of trademarks owned by third parties, which normally leads to the conclusion that consumers will pay closer attention to the non-common features to distinguish the marks issue, decreasing the likelihood of confusion.

In last year’s Annual Review, we reported on a dispute between Constellation Brands Inc. (“Constellation”) and Domaines Pinnacle Inc., (“Domaines”) with respect to the application for registration by Domaines for its mark DOMAINE PINNACLE & Design in association with apple-based products (the “Domaines Mark”). The opposition by Constellation before the Trademarks Opposition Board was based on its allegations of the likelihood of confusion with Constellation’s registered trademarks PINNACLES and PINNACLES RANCHES used in association with wine (the “Constellation Mark”).

On appeal from the Registrar’s decision to reject Constellation’s opposition, the Federal Court determined that the Registrar erred in its decision in failing to take into account, following the reasoning by the Supreme Court of Canada in Masterpiece Inc. v. Alavida Lifestyles Inc., 2011 SCC 27 (“Masterpiece”), that the opponents’ registered word mark PINNACLES could have a different style of lettering, colour, or design that could have been similar to the applicant Domaines’ Mark DOMAINE PINNACLE & Design (Constellation Brands Inc. v. Domaines Pinnacle Inc., 2015 FC 1083).

Domaines appealed the decision of the Federal Court to the Federal Court of Appeal.

The Federal Court of Appeal, at 2016 FCA 302, determined that the lower court used the wrong standard of review, as it applied the standard of whether the Registrar’s decision was correct rather than whether it was reasonable.

The Federal Court of Appeal pointed out that the lower court could conduct a review of the Registrar’s decision on the basis of correctness or a de novo review only if it accepted the new evidence submitted by Constellation on the appeal to the Federal Court. Further, the Federal Court of Appeal found that the Registrar did cite the Masterpiece decision in its analysis of confusion and held that its application of the precedent was within the range of reasonable outcomes open to the Registrar in making its findings of confusion.

The Federal Court of Appeal was satisfied that even if Constellation chose in the future to use the same font as used in Domaines’ Mark, the combination of the word and design in Domaines’ PINNACLE & Design mark was sufficiently distinctive and different from Constellation’s word mark PINNACLES. In this regard, the Federal Court of Appeal noted the Registrar’s finding that neither the Constellation Mark nor the Domaines Mark possessed a high degree of distinctiveness as the common element of both marks, the word “Pinnacle” was a commonly used term.

Accordingly, the Federal Court of Appeal allowed Domaines’ appeal and affirmed the Registrar’s decision to allow the registration of the Domaines Mark.

2. Use

Constellation also received a decision in another dispute in 2016 in which it opposed the registration of the trademark HEMISFERIO by Sociedad Vinicola Miguel Torres, S.A. (“Miguel Torres”), used in association with wines since at least as early as October 28, 2011 (the “Miguel Torres Mark”): Constellation Brands Québec Inc. v. Sociedad Vinicola Miguel Torres, S.A., 2016 TMOB 4.

The opposition proceeding concerned whether the applicant Miguel Torres discharged its legal onus of establishing, on a balance of probabilities, that it had first used the Miguel Torres Mark on the dated claimed in the application, October 28, 2011.

The initial evidentiary burden is on the opponent, Constellation, to adduce some evidence that Miguel Torres has failed to show use in Canada as of the date claimed. Thereafter, the applicant must respond and discharge its legal onus.

Constellation alleged that the evidence of an invoice provided by Miguel Torres to substantiate its date of first use concerning a sale of wine from Chile to Canada referencing an item “HEMISFERIO SB 750cc” indicated that there was no first use as claimed in Miguel Torres’ application. This invoice indicated an arrival date for the goods shipped of January 26, 2012. In short, Constellation alleged that the transfer of possession of the goods into Canada took place in January 2012, not October 28, 2011. Mere evidence of sales located abroad at a particular date, but destined for Canada at a later date, cannot substantiate the former as the date of first use of the mark in question within the meaning of “use” in Canada pursuant to s. 4(1) of the Act.

Accordingly, the Registrar rejected the application for registration of Miguel Torres despite the general assertion of Miguel Torres of its claimed first use date.

In Restaurants La Pizzaiolle Inc. v. Pizzaiolo Restaurants Inc., 2016 FCA 265, the court heard an appeal of the lower court decision on which we reported in last year’s Annual Review (2015 FC 240).

In this case the Registrar refused registration by Pizzaiolo Restaurants Inc. (“PRI”) of the word mark PIZZAIOLO, but allowed the registration of PRI’s design mark incorporating the word mark PIZZAIOLO (the “Design Mark”).

The Federal Court overturned the decision of the Registrar to register the Design Mark incorporating the word PIZZAIOLO in association with gourmet pizzas and restaurant services.

Specifically, the Federal Court found that there was a likelihood of confusion between the Design Mark and the registered trademarks LA PIZZAIOLLE or PIZZAIOLLE owned by the opponent, Restaurants La Pizzaiolle Inc. (“LPI”). This likelihood of confusion extended to the Design Mark.

The Federal Court of Appeal reviewed whether the lower court properly applied the reasonableness standard of review of the Registrar’s decision. The Federal Court of Appeal found that the lower court did properly apply the reasonableness standard of review in finding that the Registrar failed to take into account the right, conferred upon the opponent LPI by registration of the mark LA PIZZAIOLLE by LPI, to use that mark in any size and with any style of lettering, colour, or design.

Accordingly, the Federal Court of Appeal upheld the lower court’s decision to refuse registration of the Design Mark and dismissed PRI’s appeal.

3. Goodwill/Passing-off

In Sadhu Singh Hamdard Trust v. Navsun Holdings Ltd., 2016 FCA 69, the court dealt with the issue of goodwill in a trademark in a copyright infringement and passing-off case.

At trial, the Federal Court dismissed the infringement and passing-off claim of Sadhu Sing Hamdard Trust (“Hamdard Trust”) against Navsun Holdings Ltd. and 61783235 Canada Inc. (the “Bains Parties”) and Master Web Inc.

Hamdard Trust is the owner and publisher of a Punjabi-language daily newspaper in India called the “Ajit Daily”, which has been published since 1955 and is well known among the Punjabi population in India. Since 2002 an on-line version has been available. However, only a small number of subscriptions have been sold in Canada.

The Bains Parties own and publish a Canadian Punjabi-language newspaper called the “Ajit Weekly”, which has been published in Canada since 1993. Since 1998, an on-line version has been available.

There has been a history of litigation world-wide between Hamdard Trust and the Bains Parties.

With respect to the passing-off claim, the Federal Court found that it failed because Hamdard Trust did not establish that it possessed goodwill in the trademark in Canada for which it was basing this claim. There was no survey or other independent reputable evidence to find that Hamdard Trust’s Ajit Daily has commercial goodwill or is famous in Canada, as the only evidence presented was of seven subscribers in Canada in 2010.

The Federal Court of Appeal determined that this was an error in law because use of a trademark in Canada is not a necessary pre-condition for the existence of goodwill within Canadian law. The requisite goodwill within Canada can be shown by virtue of the reputation of the plaintiff’s trademark even though the plaintiff does not use the trademark in Canada. In this regard, the Federal Court of Appeal cited the well-known case of Orkin Exterminating Co. Inc. v. Pestco Co. of Canada Ltd., 1985 CanLII 157 (ON CA).

The Federal Court of Appeal identified that there was some evidence before the lower court to indicate that Hamdard Trust’s Ajit Daily enjoyed a reputation in Canada. Because the lower court failed to evaluate this evidence, the appeal of Hamdard Trust was allowed.

The Federal Court of Appeal ordered that the matter be remitted back to the Federal Court to reassess the evidence. Hamdard Trust’s request that it be allowed to file further evidence with respect to its reputation in Canada was deferred to the lower court to determine how its reassessment should be conducted.

4. Personal Liability

Once again in 2016, Trans-High Corporation (“Trans-High”) was active in asserting its trademark rights against retailers using its HIGH TIMES registered trademark: Trans-High Corp. v. Conscious Consumption Inc., 2016 FC 949.

As in Trans-High Corp. v. High Times Smokeshop and Gifts Inc., 2013 FC 1190, Trans-High was successful in its infringement, passing-off, and depreciation of goodwill action. As in 2013, the court ordered damages in the sum of $25,000 against the defendant. However, in 2016, Trans-High also pursued personal liability against the individual defendants who were directors and owners of the corporate defendant operating the retail store that infringed Trans-High’s trademarks.

These individuals refused to participate in the court process although duly served and given notice of the claims brought against them.

In brief reasons, the Federal Court held that corporate documents and social media postings clearly indicated that the two individual defendants were owners and directing minds of the corporate defendant and that they willfully infringed Trans-High’s trademark right such that this conduct was not a legitimate exercise of their corporate duties as officers, directors, or controlling minds of the corporate defendant.

Accordingly, these individual defendants were also jointly and severally liable for the damages awarded against the corporate defendant.

In Lam v. Chanel S. de R.L., 2016 FCA 111, the court heard the appeal of a decision of the Federal Court in which it ordered compensatory damages in the sum of $64,000, punitive damages in the sum of $250,000, and costs in the sum of $66,000 against the defendants in the action, including personal liability against Annie Pui Kwan Lam (“Ms. Lam”), arising out of the sale of counterfeit merchandise of Chanel S. de R.L. (“Chanel”). The damage awards were noted by the Federal Court of Appeal as being significant and outstripping awards in many previous cases.

The Federal Court of Appeal found that there was ambiguity in the lower court’s reasons for judgment against Ms. Lam personally concerning the infringement that occurred, which required the lower court to resolve and re-determine the quantum of damages and costs assessed. Specifically, in issue was the ambiguity in the findings regarding the extent of Ms. Lam’s involvement in the acts of infringement. In short, the Federal Court of Appeal found that “an award of this magnitude” called for an explanation founded on the applicable legal tests and specific facts of the case that was “more expansive” than the explanation given by the trial judge.

As a result, in Chanel S. de R.L. v Lam Chan Kee Co., 2016 FC 987, the Federal Court reviewed and provided further reasons concerning Ms. Lam’s personal liability to the damage awards.

The Federal Court confirmed Ms. Lam’s personal liability jointly and severally with the other corporate defendants for all of the damage awards. Ms. Lam was found to be at all materials times the controlling mind of the corporate defendants.

Specifically, the corporate changes whereby Ms. Lam transferred and sold her business to her children did not change Ms. Lam’s personal liability. The Federal Court of Appeal was highly suspicious of corporate changes approved and signed by Ms. Lam in 2011 that were only filed in 2013, after Chanel served its statement of claim on Ms. Lam. Further, Ms. Lam failed to show that her children had paid the balance of the sale price for the business she owned. As well, the Federal Court noted that it was not clear as to whether staff at Ms. Lam’s business were notified of the change in ownership, Ms. Lam continued to be the landlord of the business premises even after the sale of the business, and she was still benefitting from ongoing profits of the business after the sale.

Other factors in support of Ms. Lam as the controlling mind of the corporate defendants were that Ms. Lam did not talk to her children when the cease and desist letter was delivered by the plaintiff, and Ms. Lam, not her children, hired legal counsel when the action was commenced.

In support of the quantum of the damages awarded, the Federal Court noted that a company controlled by Ms. Lam was also successfully sued for selling counterfeit Chanel products in 2006 whereby Ms. Lam entered into a consent judgment restraining her from selling counterfeit Chanel products and requiring her to pay damages in the sum of $6,000.

While the damages awarded against Ms. Lam were large, the Federal Court noted several other decisions of that court in which the defendants in trademark infringement proceedings were ordered to pay significant damages:

- $100,000 in punitive damages (Entral Group International Inc. v. MCUE Enterprises Corp., 2010 FC 606);

- $250,000 in punitive damages and $200,000 in compensatory damages (Louis Vuitton Malletier S.A. v. Singga Enterprises (Canada) Inc., 2011 FC 776);

- $696,000 in punitive damages and $1,392,000 in compensatory damages (Guccio Gucci SPA and Gucci America Inc. v. Bobby Bhatia, (unreported) Federal Court File No. T-1556-14); and

- $200,000 in punitive damages and $580,000 in compensatory damages (Louis Vuitton Malletier S.A. v. 486353 BC Ltd., 2008 BCSC 799).

It should be noted that Ms. Lam has once again appealed the Federal Court’s decision against her to the Federal Court of Appeal. We will have to await whether the Federal Court of Appeal will once again take issue with the lower court’s damage awards against Ms. Lam.

5. Geographic Location

In MC Imports Inc. v. AFOD Ltd., 2016 FCA 60, the court dealt with the validity of a trademark as a geographical location.

The appellant, MC Imports Inc. (“MCI”) and its predecessors in title imported and sold fish and shrimp sauce food products in Canada since 1975 under the trademark LINGAYEN (the “MCI Mark”). In 2003, the MCI Mark was registered in Canada.

MCI commenced an action against AFOD Ltd. (“AFOD”) for trademark infringement and passing-off for the use of the words “Lingayen Style” in smaller script below AFOD’s trademark NAPAKASARAP on its fish sauce products. In response, AFOD counterclaimed against MCI challenging the validity of the registration of the MCI Mark in Canada based on the allegation that at the time of registration in Canada, the MCI Mark was clearly descriptive of the place of origin of the goods, the municipality of Lingayen in the Philippines, where the fish products originated. As such, AFOD claimed MCI was in breach of s. 12(1)(b) of the Act.

At the summary trial of the action and counterclaim, the trial judge dismissed MCI’s infringement action and found that the MCI Mark was not registerable as it was clearly descriptive contrary to s. 12(1)(b) of the Act.

Interestingly, the Court of Appeal was left to decide between two decisions of the Federal Court as to the proper test to be applied in the case of a mark alleged to be clearly descriptive of a geographic place: Consorzio del Prosciutto di Parma v. Maple Leaf Meats Inc., [2001] 2 FC 536 (Fed. T.D.) (“Parma”) and Sociedad Agricola Santa Teresa Ltda. c. Vina Leyda Ltda., 2007 FC 1301 (“Leyda”). In Parma, it was found necessary to ask whether the ordinary consumer would recognize the mark as relating to the place of origin. However, in Leyda, the court set aside the ordinary consumer’s recognition and understanding of the mark as irrelevant, asking only whether it clearly describes the actual place of origin of the goods or services.

The Court of Appeal rejected the Parma approach and laid out the analysis to be followed. The Court of Appeal held that it must determine whether a geographic name is unregisterable as a trademark because it is clearly descriptive of a place of origin by first determining whether the trademark is a geographical name; second, by determining the place of origin of the goods or services; and third, by assessing the trademark owner’s assertions of prior use, if any.

In applying the first branch of the test in making a determination of whether the trademark is a geographical name, where there are multiple meanings, the court must look for the predominant meaning. In making this determination, the court must rely on the ordinary consumer of the goods or services in issue with which the trademark is used and not the ordinary consumer in the sense of the general public as a whole.

With respect to the second branch of the test, if the goods and services originate in the place referred to by the trademark, then the trademark is clearly descriptive of the place of origin. The perspective of the ordinary consumer is unnecessary in this circumstance. In this regard, trademark applicants should not be allowed to benefit from a consumer’s lack of knowledge of geography. If the trademark refers to a geographic place that is not the actual place of origin of the goods or services, then it cannot be clearly descriptive of the place of origin. In such circumstances, it is misdescriptive and further analysis is required to determine whether it is deceptively so.

With respect to the third branch of the test, the court must inquire whether, despite being clearly descriptive, the trademark owner’s use of the mark prior to registration was such that the mark had acquired such distinctiveness as a trademark of the owner so as to avoid invalidity of a registration.

In this regard, consumer perception is highly relevant. Evidence of people who actually use the goods or services must be sufficient to show the mark has acquired distinctiveness so that the mark in issue is associated with the trademark owner rather than merely a geographic location.

However, on the facts of this case, the mark LINGAYEN was found to be a geographical name under the first branch of the test and the products sold in association with that mark originated from that geographic place. Accordingly, the MCI Mark was clearly descriptive of a geographic location and the Court of Appeal was left with the third branch of the test to determine. In this regard, MCI only provided evidence that its product had been continuously sold since 1975 in association with the MCI Mark along with one expert’s affidavit that the MCI Mark had “likely” acquired distinctiveness in the minds of consumers. The Court of Appeal found that this was insufficient to show that the MCI Mark had acquired distinctiveness to overcome invalidity under s. 12(1)(b) of the Act as being a mark clearly descriptive of a geographic location.

As the MCI Mark was invalid, MCI’s claim for trademark infringement failed. With respect to the passing-off claim, the Court of Appeal identified the three elements of such a claim: the existence of reputation (or goodwill) in the mark, misrepresentation by the defendant in the action that leads to confusion or the likelihood of confusion, and damages to the plaintiff arising from the confusion or likelihood of confusion.

Interestingly, the Court of Appeal dismissed the argument of AFOD that MCI could not have any reputation in the MCI Mark as its predecessor in title had assigned the MCI Mark to it specifically excluding the goodwill associated with the MCI Mark.

The Court of Appeal stated that such an assignment could have been done for tax reasons but this did “not mean the trademark has somehow been stripped of its goodwill within the meaning contemplated in this analysis, which looks to the reputation and earning power of the trademark”.

In any event, the Court of Appeal dismissed the passing-off claim on the basis that there was no misrepresentation leading to deception of the public by AFOD in the use of the words “Lingayen Style” on its products.

Accordingly, the appeal of MCI failed.

6. Section 45

Last year we reported on a Federal Court decision in Gouverneur Inc. v. One Group LLC, 2015 FC 128, in which the court reversed the decision of the Registrar who refused to expunge under s. 45 of the Act the trademark STK of the One Group LLC (“One Group”) registered in association with “bar services, restaurants”. Pursuant to s. 45 of the Act, a trademark registration can be expunged if it has not been used by the owner in the preceding three-year period prior to notification under the provision.

On the appeal to the Federal Court of Appeal in Gouverneur Inc. v. One Group LLC, 2016 FCA 109, Gouverneur Inc. (“Gouverneur”) was successful in having the Registrar’s decision reinstated expunging the registered trademark of the One Group. In brief reasons, the Court of Appeal emphasized that deference must be given to the Registrar under s. 45 of the Act and that the Registrar must be given “broad discretion” in expungement proceedings. As a result, the courts should not disturb the Registrar’s findings of fact except in those circumstances where such findings are clearly not correct.

On the facts of the case, the Federal Court of Appeal reinstated the One Group’s trademark registration as it was not prepared to find a clear error in the Registrar’s decision. In the view of the Federal Court of Appeal, the Registrar’s decision, as reported in last year’s Annual Review, fell within the range of reasonable outcomes.

Ultimately, this case is a reminder that there is a “special circumstance” exception to non-use by an owner that can be used to preserve registrations that are liable to be expunged under s. 45 of the Act.

The criteria for this is worth repeating:

- the length of time during which the trademark has not been used;

- whether the reasons for non-use were beyond the registered owner’s control; and

- whether the registered owner has a serious intention to shortly resume use of the trademark.

This case is also a reminder from the Federal Court of Appeal that there is a general willingness of the Registrar to preserve registrations and that, where the Registrar makes findings of fact in support of preserving a registration, the court’s deference to those findings on appeal presents a potentially difficult hurdle to overcome.

7. Joinder and Intervener Status

In the 2014 edition of Annual Review, we reported on the issue of the right to intervene in an appeal of a decision of the Federal Court with respect to s. 45 of the Act. In 2016, this Federal Court decision was appealed to the Federal Court of Appeal in Bauer Hockey Corp. v. Easton Sports Canada Inc., 2016 FCA 44.

The essential facts concern the trademark infringement action in the Federal Court brought by Bauer Hockey Canada (“Bauer”) against Easton Sports Canada Inc. (“Easton”) and Sport Maska Inc. doing business as Reebok-CCM Hockey (“CCM”), which Easton and CCM defended. However, Easton also brought a separate proceeding before the Trademarks Opposition Board for expungement of the Bauer registered trademark pursuant to s. 45 of the Act for non-use in the preceding three-year period. Easton was successful in having the Bauer registered trademark expunged pursuant to s. 45 of the Act but settled its infringement action dispute with Bauer, whereby Easton would not challenge Bauer’s appeal to the Federal Court of the expungement decision made under s. 45 of the Act.

However, the other defendant in the Bauer infringement action, CCM, sought to intervene in this appeal in place of Easton. The Federal Court upheld the Prothonotary’s decision to deny CCM’s motion to intervene in lieu of Easton in the s. 45 appeal. In reviewing the factors as to whether intervener status will be granted, the Federal Court found CCM met only two of the five factors to consider in determining intervener status. CCM appealed this decision again.

On the appeal, the Federal Court of Appeal undertook a lengthy review of the matter and upheld the decision of the lower court judge and the Prothonotary to refuse CCM’s request to be granted intervener status. While the Federal Court of Appeal stated that the Prothonotary ought to have considered that there was a public interest component in the s. 45 proceedings, the existence of a public interest component did not, in the present matter, outweigh other considerations that militated against granting intervener status. In this regard, the Federal Court of Appeal noted that s. 45 proceedings can be initiated and conducted by anyone wishing to challenge the registration of a trademark it believes has not been used in the past three years in order to clear the trademark registry of invalid trademarks. However, the public interest aspect did not elevate s. 45 proceedings to a level comparable to cases that “affect large segments of the population or raise constitutional issues” raising the public interest factor to override all others. In short, when all of the factors were considered, the public nature of the expungement proceedings under s. 45 of the Act did not tip the scale in favour of allowing CCM to intervene in the proceeding.

The Federal Court of Appeal noted Bauer’s assertion that existing contractual arrangements between Bauer and CCM precluded CCM from challenging the use or registration of the Bauer Mark in issue. Bauer was relying on this argument in defending CCM’s counterclaim against Bauer in the infringement action where CCM alleged invalidity of Bauer’s Mark. However, the Federal Court of Appeal agreed with Bauer that if CCM was an intervenor in the s. 45 appeal, Bauer could not raise this argument in the s. 45 appeal as such an appeal proceeding would only be reviewing the decision of the Registrar to expunge the Bauer trademark registration for non-use applying the appropriate standard of review.

Further, the validity of Bauer’s trademark registration was a live issue in the infringement action brought by Bauer in which CCM defended by way of counterclaim challenging the validity of Bauer’s trademark registration. In effect, the question raised in the s. 45 proceeding was also raised in the litigation conducted by the parties so that CCM would suffer no prejudice if its intervener status was rejected in the s. 45 proceedings.

Finally, the Federal Court of Appeal noted that CCM could have pursued its own s. 45 proceedings at any time but chose not to do so.

However, the story does not end there as Bauer still had to pursue its appeal of the decision of the Registrar to expunge its registered trademark pursuant to s. 45 of the Act. This matter was heard by the Federal Court and decided in Bauer Hockey Corp. v. Easton Hockey Canada, Inc., 2016 FC 1373.

As mentioned above, Easton did not dispute the appeal to the Federal Court by Bauer pursuant to its settlement with Bauer. The Federal Court allowed Bauer’s appeal and quashed the decision of the Registrar to expunge Bauer’s trademark registration under s. 45 of the Act.

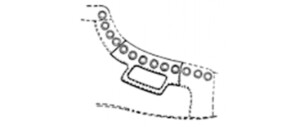

The key issue on this appeal to the Federal Court was whether Bauer’s registered trademark for its skates’ eyestay design set out below was used within the previous three years from when notice was given under s. 45 of the Act (the “Bauer Mark”)

Specifically, the issue turned on:

- whether the Bauer Mark as used in the marketplace was consistent with the Bauer Mark as it was registered; and

- whether the use of the Bauer Mark enured to the benefit of Bauer, the registered owner, through proper licensing.

The Federal Court reviewed the matter on the basis of new evidence filed by Bauer and the standard of whether the Registrar’s decision was correctness.

With respect to the first issue, the Federal Court found that the differences in how the Bauer Mark was used as opposed to how it appeared in the trademark registration were not significant. The Bauer Mark as used by Bauer in the marketplace included the word “Bauer” in the rectangular box area along the skates’ eyestays, whereas the trademark registration did not have the word “Bauer” in this area.

With respect to the second issue, Bauer provided further evidence of a licensing agreement to show that the use of the Bauer Mark during the relevant three-year period enured to the benefit of the trademark owner, Bauer.

As a result, Bauer was successful in maintaining the Bauer Mark on the Trademark Registry.

2016 was also a busy year for the drinks company, Constellation, as it was also involved in a number of proceedings, including a request for expungement of Constellation’s trademark DA VINCI registered in association with distilled alcohol and liqueurs (the “Constellation Mark”) for non-use during the previous three-year period pursuant to s. 45 of the Act. This s. 45 dispute also raised issues of joinder as a party or intervener status in such proceedings as set out in Constellation Brands Quebec Inc. v. Smart & Biggar, 2016 FC 605.

The dispute initially arose out of the application of Casa Vinicola Botter Carlo & Co. (“Botter”) for registration of Botter’s mark DIVICI and the application of Dallevigne S.P.A. (“Dallevigne”) for registration of Dallevigne’s mark of CANTINE LEONARDO DA VINCI (the “Dallevigne Mark”). Constellation commenced separate opposition proceedings based on its previously registered Constellation Mark against Botter and Dallevigne. The Registrar rejected Constellation’s opposition against Botter and allowed registration of the DIVICI Mark. However, the Registrar refused registration of Dallevigne’s application to register the CANTINE LEONARDO DA VINCI mark based on the likelihood of confusion with the Constellation Mark.

In parallel proceedings brought by Botter’s counsel under s. 45 of the Act, the Constellation Mark was expunged. Constellation appealed that decision to the Federal Court. Dallevigne sought to be added as a party to these s. 45 proceedings as it did not originally request the notice of expungement and was not a party to those proceedings. Further, Dallevigne sought a stay of the decision of the Registrar to refuse application to register the Dallevigne Mark pending the outcome of the s. 45 proceedings.

Dallevigne could not commence its own s. 45 proceeding as they had already been brought by Botter’s counsel. The practice of CIPO is to not allow parallel expungement proceedings under s. 45 of the Act for the same mark.

Problematic for Dallevigne was the fact that Botter’s counsel gave notice that it did not intend to defend Constellation’s appeal of the decision in the s. 45 proceedings as Botter succeeded in getting its mark registered. If Constellation was successful in maintaining the Constellation Mark on the register, then Dallevigne’s avenue to overturn the decision to refuse registration of its CANTINE LEONARDO DA VINCI mark would be foreclosed as Constellation’s prior registration of its mark DA VINCI would remain valid and the basis for the likelihood of confusion.

The Federal Court was charged with determining an appeal whether the Prothonotary’s decision to order that Dallevigne be joined as a party to the appeal by Constellation of the expungement of the Constellation Mark pursuant to s. 45 of the Act should be upheld, or in the alternative whether Dallevigne should be granted intervener status in the s. 45 appeal proceedings.

The Federal Court held that while it was possible under the rules of court applicable to s. 45 proceedings for Dallevigne to be added as a party to the proceedings, it was not satisfied that on the facts Dallevigne was an entity who may be “directly affected” by the outcome of the proceedings or was a “necessary party” as required by such rules and therefore ought to be made a party.

The requirement that a person be “directly affected” by the proceedings to be joined as a party means a person who could have brought the appeal themselves. The Federal Court stated that if counsel to Botter had failed to get an order for expungement pursuant to s. 45 of the Act, it could not see how Dallevigne could have appealed that decision. Simply put, appeals are limited to the parties to the proceedings or intervenors.

Further, the Federal Court found that Dallevigne was not a “necessary party” as required by the Federal Court rules as there was no claim being made against it, nor was it necessary that it be joined so as to bind it on the appeal.

With respect to the alternative argument of Dallevigne that it should be granted intervener status in the appeal of the s. 45 decision, the Federal Court relied on the Bauer Hockey Corp. v. Easton Sports Canada Inc. decision of the Federal Court of Appeal noted above (“Bauer FCA”).

However, the Federal Court came to a different result and allowed Dallevigne intervener status. The Federal Court stated that this was not a situation where Dallevigne was gaining a tactical advantage where similar arguments were being advanced in other proceedings. Further, the Federal Court found that Dallevigne’s participation would have a likely effect of simplifying and expediting the opposition proceedings which were stayed.

With respect to the test of whether Dallevigne was “directly affected” by the appeal proceeding so as to qualify as an intervener, the Federal Court found that Dallevigne met this test despite its view of this factor in relation to its findings that Dallevigne was not a proper party to the appeal proceedings under s. 45 of the Act. In effect, with respect to the context of meeting the qualifications of an intervener, as opposed to a proper party to the proceedings, the Federal Court seems to have lowered the standard in the circumstances of an intervener application.

While the Federal Court noted that in the Bauer FCA case, and on the facts before it, the party seeking intervention was in reality seeking to be substituted for another party, the facts of the case before it showed that the opposition appeal inevitably turned on the expungement decision and as such intervener status was more than a mere technical advantage in the opposition appeal.

Further, the Federal Court pointed out that by the time pleadings were concluded in the opposition proceeding involving Dallevigne, Botter’s counsel had already moved to expunge the Constellation Mark and Dallevigne was foreclosed from bringing its own s. 45 proceedings.

It is worth noting that the Federal Court commented that CIPO may well have to change its practice of not allowing parallel expungement requests for the same mark.

8. False or Misleading Statements

In E. Mishan & Sons, Inc. v. Supertek Canada Inc., 2016 FC 986 (“Supertek”) we were once again reminded that in intellectual property disputes parties should be cognizant of the importance of s. 7(a) of the Act, which prohibits a person from making “false or misleading statements tending to discredit the business, goods or services of a competitor”.

The plaintiff, E. Mishan & Sons Inc. (“Emson”) was unsuccessful in proving its patent infringement claim against Supertek Canada Inc. (“Supertek”) with respect to Emson’s expandable hose product called “Xhose” as Emson’s patent was found to be invalid. However, Supertek alleged by way of counterclaim that Emson had made, in breach of s. 7(a) of the Act, false or misleading statements to Supertek’s customer Canadian Tire to whom Supertek supplied its product that Emson wrongly claimed infringed Emson’s patent.

Prior to the commencement of the patent infringement action, Supertek allegedly approached Canadian Tire offering to sell Canadian Tire its competing expanding hose product called “Pocket Hose” and to provide an indemnity for any lawsuit brought by Emson.

Emson heard that Supertek was trying to sell its Pocket Hose product to Canadian Tire and contacted Canadian Tire. Canadian Tire understood Emson’s position to be that it was threatening legal action against it if Canadian Tire continued to advertise Supertek’s Pocket Hose product.

In response to the situation, Canadian Tire offered Emson two choices: allow Canadian Tire to make a one-time promotion of Supertek’s Pocket Hose after which Canadian Tire would stick with Emson’s Xhose; or, alternatively, Emson could sue Canadian Tire for patent infringement, which could result in the end of any business between Emson and Canadian Tire.

Based on this evidence the Federal Court held that Emson had made, as a consequence of the finding that Supertek had not infringed Emson’s patent, false and misleading statements within the meaning of s. 7(a) of the Act to Canadian Tire, a customer of Supertek.

However, the Federal Court did not find a causal link between the threats made by Emson to Canadian Tire and a loss of sales by Supertek to Canadian Tire. In effect, the evidence showed that while Canadian Tire found the discussions with Emson “stressful”, Canadian Tire was happy with Emson’s Xhose product and intended to continue to sell it. The purchase of Supertek’s Pocket Hose was a one-time only buy and Canadian Tire did not want to have an inventory problem by handling two product lines. Ultimately, the discussions between Emson and Canadian Tire played no part in the decision of Canadian Tire to not sell Supertek’s Pocket Hose.

Accordingly, Supertek’s claim under s. 7(a) of the Act against Emson failed.

In Excalibre Oil Tools Ltd. v. Advantage Products Inc., 2016 FC 1279, the Federal Court came to a different conclusion with respect to a claim under s. 7(a) of the Act. In this case, the plaintiff, Advantage Products Inc. (“API”) was also unsuccessful in its patent infringement action against the defendant Excalibre Oil Tools Ltd. (“Excalibre”) and part of the patent portfolio of API was found to be invalid.

In response, Excalibre alleged it had suffered damages as a result of cease and desist letters that were sent by API to Excalibre’s customers, invoking s. 7(a) of the Act against API.

The court, following the Supertek case, found that the cease and desist letters sent to Excalibre’s customers were not merely informative of the state of matters between API and Excalibre in their dispute, but were threatening litigation and as such the letters were in breach of s. 7(a) of the Act. Specifically, the letters contemplated amending the patent infringement litigation brought by API to include Excalibre’s customers.

Excalibre’s customers provided evidence at trial that they changed their purchasing decisions and no longer purchased Excalibre’s products because of the cease and desist letters from API as opposed to the finding in the Supertek case that the customers ultimately did not change their purchasing plans as a result of the threats made. Accordingly, the Federal Court ordered that damages be paid by API to Excalibre for breach of s. 7(a) of the Act for false and misleading statements, the quantum of which was reserved by way of a reference after trial.

It should be noted that this decision has been appealed in the Federal Court of Appeal.

In another case in 2016 involving allegations of false and misleading statements in breach of s. 7(a) of the Act, Bell Canada (“Bell”) sought an interlocutory injunction against Cogeco Cable Canada GP Inc. (“Cogeco”) with regard to an advertising campaign on the website whereby Cogeco used the phrase “the best Internet experience in your neighbourhood” to promote Cogeco’s hybrid fiber co-axial cable (“Cable/HFC”) internet service: Bell Canada v. Cogeco Cable Canada GP Inc., 2016 ONSC 6044.

In this case, Bell asserted that its fiber-to-the-home (“FTTH”) technology was a superior Internet delivery system, which Cogeco itself recognized in its 2016 Annual Report. Further the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission (“CRTC”) had released a report that FTTF out performs Cable/HFC, including providing higher Internet delivery speed.

The court cited the well-known three-part test for an interlocutory injunction:

- whether the moving party has demonstrated that there is a serious question to be tried;

- whether the moving party will suffer irreparable harm if an injunction is not granted; and

- whether the balance of convenience favours granting the injunction.

The court found that based on the CRTC report, of which Cogeco was obviously well aware, there was a serious question to be tried regarding whether the alleged misrepresentation was made knowingly or recklessly.

Further, the court was satisfied that Bell would suffer irreparable harm for which it could not be compensated in damages if Cogeco continued to advertise that it provided “the best Internet experience in your neighbourhood”. The Ontario Court held that it would be difficult, if not impossible, to determine with any certainty which potential or existing customers were misled by the claim that Cogeco is the best, and which customers or potential customers made their choices for reasons unrelated to this advertising claim.

Finally, the Ontario Court was satisfied that the balance of convenience favoured granting of the injunction. In this regard, the Ontario Court noted that the advertising was during the Fall “Back-to-School” marketing season which is apparently a key time period to attract new customers and the cost for Cogeco to remove the key word “best” from its advertising phrase on Cogeco’s website would be insignificant.

As a result, despite stating that it had a general reluctance to intervene in a very competitive marketplace, the Ontario Court granted the interlocutory injunction.

9. Nature of the Goods or Trade

In Specialty Software Inc. v. Bewatec Kommunikationstechnik GmbH, 2016 FC 223, the court heard an appeal of Specialty Software Inc. (“Specialty”) from the decision of the Registrar to expunge its registered trademark for non-use during the previous three-year period pursuant to s. 45 of the Act.

The s. 45 proceeding was brought by Bewatec Kommunicationstechnik GmbH (“Bewatec”) and Specialty failed to provide any evidence in the proceeding before the Registrar.

On appeal, Specialty provided fresh evidence of use of its registered trademark in relation to software used by hospitals and physicians to track patients’ medications. However, Bewatec took issue with this evidence, arguing that Specialty’s actual use of its trademark was in relation to services, not goods as set-out in its registration.

Specialty used to sell its software in a tangible form on disks. However, Specialty’s clients can now obtain access to its software over the Internet from Specialty. As a result, Bewatec argued that Specialty was offering a service in the form of access to a website and therefore Specialty had not used its trademark as claimed in its registration in relation to goods in the preceding three year period.

However, the Federal Court disagreed with Bewatec, stating that “there has been no real change in what Specialty is selling”. The change related to the means by which the software was transferred to clients, not the actual nature of Specialty’s use of its trademark.

This controversial decision is currently under appeal to the Federal Court of Appeal.

10. Distinctiveness

In Richtree Market Restaurants Inc. v. Mövenpick Holding AG, 2016 FC 1046, the court heard the appeal of Richtree Market Restaurants Inc. (“Richtree”) with respect to the Registrar’s decision to allow Mövenpick Holding AG (“Mövenpick”) to register its trademark MARCHÉ & Wave Design (the “Mövenpick Mark”).

Richtree had opposed Mövenpick’s application for registration based on a number of grounds, but appealed only on the ground of opposition. Specifically, Richtree alleged that the Mövenpick Mark was not registerable because it was not distinctive. Other trademarks, trade-names or business names were used by numerous third parties that contained the word “marché” or “market” in association with identical services.

In reviewing the decision of the Registrar on the standard of whether it was reasonable, the Federal Court concluded that the Registrar’s decision should not be overturned and its finding that the Mövenpick Mark was sufficiently distinctive to register was not unreasonable.

The court stated that “even if the word ‘marché’ may not be in and of itself immediately or inherently distinctive”, it was prepared to hold the Registrar’s finding reasonable. Simply put, despite numerous businesses using the word “market” or “marché” in their name and that the word element was the dominant element in the Mövenpick Mark, the majority of the businesses were not restaurants. As a result, Richtree’s attack on the distinctiveness of the Mövenpick Mark failed.

In Wenger S.A. v. Travel Way Group International Inc., 2016 FC 347, the court dealt with allegations of trademark infringement and passing-off in an action brought by Wenger S.A. (“Wenger”), the maker of the famous Swiss Army Knives, with respect to its stylized cross logos registered in association with, among other things, luggage and bags (the “Wenger Marks”):

Wenger brought its action against Travelway Group International Inc. (“Travelway”), which manufactured and distributed travel related products, with respect to Travelway’s “S” in a cross logo design and a modification of its logos whereby the “S” was difficult to see or was eliminated (the “Travelway Marks”):

In reviewing the analysis for whether confusion exists between the Wenger Marks and the Travelway Marks pursuant to s. 6(5) of the Act, the court noted that the degree of resemblance between the marks in issue is “generally the most important component of the confusion analysis”. In considering this factor, the court did find that there was a level of resemblance between the Wenger Marks and the disappearing “S” or missing “S” logo designs of the Travelway Marks that warranted further inquiry with respect to the confusion analysis.

In this regard, the court was not convinced that the Wenger Marks had acquired distinctiveness such that they had become known to consumers as originating from one particular source, Wenger.

While the court noted that the Wenger Marks were on millions of pieces of luggage sold by Wenger since 2003 and that Wenger had spent considerable sums marketing and promoting these goods, it was not convinced that the white cross logo forming the basis of the Wenger Marks was a unique identifier of luggage emanating from Wenger and that it exclusively continued the celebrated tradition of the Swiss Army Knife. The court identified that there were third parties that used a similar white cross logo, not the least of which is Victornix, who also holds a tradition linked to a Swiss Army Knife.

Further, the court was convinced, on the balance of the evidence concerning surrounding circumstances of the matter, that the average consumer somewhat in a hurry would not be confused.

Specifically, the court noted that the missing “S” logo was exclusively used by Travelway on zipper pulls that are quite small on luggage and bag wares, such that an average consumer somewhat in a hurry would not even notice this type of detail. Further, the court was dismissive of the evidence of actual confusion provided by Wenger. Mistakes in retail advertising by Canadian Tire and Walmart in three print flyers was not deemed to be evidence of “actual” confusion of consumers. The other two incidents of actual confusion were given no weight as they were not recorded and not submitted by the person who actually witnessed the alleged confusion.

Accordingly, the court dismissed Wenger’s action for trademark infringement and passing-off. However, this may not be the end of the story as this decision is currently under appeal to the Federal Court of Appeal.

The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of Jordan Thompson, an articled student with Clark Wilson LLP, in preparation of this paper.